"Food Will Win the War": Food in the Military During WWI

“Food will win the war” was Herbert Hoover’s rallying cry while in charge of the United States Food Administration during World War One. [1] This statement, although an oversimplification often made on all sides of the war, had an element of truth to it. [2] All powers involved in World War One had to deal with the issue of supplying their troops with the proper nutrition to fight a war while facing shortages, shipping and delivery issues, and quality control. Food, as a result, was one of the most important factors of the First World War and created an entire culture around it. From developing new technology, industries, organizations, and other forms of participation in the distribution and production of food for the troops, food saturated the First World War.

Theory and Planning on Rationing

America was late to the war, entering in 1917 without a very large force of men to support the European Allies, America had to catch up to their well-established counterpart’s manpower quickly. In order to do so the Selective Service Act of 1917 was deemed the most democratic process to build up a massive army in a matter of months. Thus, it was enacted, making the United States combined force of the Regular Army and National Guard (which originally was only about 208,000 men) to more than 3.7 million men with the new National Army. [3] The Americans were quickly overcome by the same issue the rest of the European troops had been facing for years now: How to supply food to their troops. Issues from the lack of proper troop diets in the Spanish American war and the questions of the quality and sanitation of meat and meat packing industries addressed in Upton Sinclair’s classic book, The Jungle, led to much debate among Americans as to how to remedy this situation before another war came knocking. [4] The Pure Food and Drug Act was established in 1906 to uphold a standard of sanitation and safety within slaughterhouses and meat plants and research into food nutrition and dietary needs began to take root in American society, preparations which would soon aid them in the war, soon to come. [5]

With a newly reorganized War Department after the Spanish American War, the United States began to examine the nutritional needs of men serving in their forces. During the previous war men serving in tropical areas had issues receiving their rations and receiving adequate rations given the harsher conditions of a tropical climate. [6] The United States was not the only country to focus heavily on a nutritious diet and just what exactly that constituted. British dieticians had determined that men only needed 3,574 calories a day to have a healthy diet but recognized that given the hard labor and conditions soldiers were meant to endure, they would need a few extra calories. [7] The rations for troops on the front lines are as follows, with the American troops receiving the highest daily caloric intake at 4,714 calories. French troops had the second-best ration system by calories, coming in at 4,466 calories, though the information was misleading since 600 of those calories were meant to be purchased by men on their daily allowance of five centimes. The British troops clocked in at 4,194 and the Germans at 4,038 calories, making their rationing the smallest of the powers. [8]

Meat was one of the most important foods to the caloric intake of troops. American soldiers were allocated 1 ¼ lbs. of meat daily, the Germans and British received 1 lb., and the French received just less than a pound. Specialty meat like turkey could be served on Thanksgiving and Christmas, if possible. [9] Vegetables were the second most important source of nutrition in ration planning. German men received over a pound of vegetables a day, the British a little over a half pound, the French had no fixed official amount, and Americans were given 1 ¼ lbs. of potatoes to work with. [10] These numbers, sadly, are only in theory. Actual rationing ranged greatly from location to location, month to month, and sometimes day to day.

In the United States, the Office of Quartermaster was the official avenue through which troops were provided food. They were developed to consolidate food production and purchasing for the military [11]. The Quartermaster controlled many different types of food in every stage of production including flour, sugar, canned vegetables, dehydrated fruits, salmon, sardines, canned milk, and fresh beef. [12] The Quartermaster Corps requested certain foods from the Food Administration purchase list and the quantity which they needed. The Food Administration would divvy up the production of these items between different producers and their capacities before it was shipped to a general supply depot where prices were decided on by the Food Purchase board. The Quartermaster Corps purchased these rations from the general supply depots nearby army posts to lessen the shipping distance and to minimize the effect that purchasing food in such quantities would have on civilian prices for these goods [13]. They also published many manuals, like the 1910 Manual for the Subsistence Department of the U.S. Army. These manuals contained guidelines on ways to select the best ration items for quality and price, as well as the proper way to purchase these items and record ration values. [14]

The Quartermaster Corps established depots for storing the different goods they procured for the military after they purchased them. There were three main types of depots. The first of which were base depots, in which they received the initial products to unload them as fast as possible and allow the ships to go back for more shipments right away. The second type of depot was closer to the front lines. They were called intermediary depots and served as the resting point for goods between the base depots and their final destination, advanced section depots. The advanced section depots were located nearest to the front lines where the supplies would be used by troops. [15]

The French and British armies had another way of providing food to their troops, through planting vegetable gardens near more permanent types of camps close to the front line. These camps usually were used for training or hospitals, since they were moved less frequently than the lines themselves and allowed for military members to cultivate and harvest their small gardens more frequently and in general take better care of them. This system was so successful that the United States Quartermaster Corps copied it and created their own Gardens Bureau to oversee the distribution of seeds and plants for these gardens. [16] For the U.S. Army, the Quartermaster Corps only provided about 40% of all the food that the military consumed. [17]

The establishment of military training schools for cooks and bakers was one of the most necessary measures for the U.S. Army and their plans to provide the American Expeditionary Force with food overseas. In 1905 the first school for bakers and cooks was established at Fort Riley, following ration problems from the Spanish American War. This was significant because they provided men with the training and resources to cook for groups of anywhere from 20-100 men. [18] The Regular Army and National Guard already had their own mess organizations, but the newly formed National Army was desperately in need of their own cooks now that they had expanded so much. These training schools filled that void. [19] Army cooks were able to use newly developed improvements to the classic rolling kitchen, like W.A. Dorsley’s compact oil-burners that could be used within these kitchens to cook more efficiently for the men. [20] The rolling kitchens were commonly known as “Liberty Kitchens” in the U.S. and were either horse-drawn or vehicle-drawn during World War One. [21] Army bakers were given technology like continuous ovens and intermittent ovens to bake bread for the military in a variety of conditions. [22]

Specially trained cooks and bakers were not the only ones who were expected to be able to provide food for soldiers though, as sometimes nurses were called on to abandon their current medical duties to provide their patients with food. “A well-fed patient has many times the chance of recovery than the wounded soldier who is served with ill-prepared food or has an insufficient diet.” [23] Since women were part of the domestic sphere, which included caring for others and cooking it was thought that this was no issue, but as the war progressed it was made clear nurses were far more valuable to the military when able to focus completely on their jobs of providing health and healing. [24]

Rationing and Reality

The realities of rationing in every military power were far less ideal than their theoretical plans that they had begun the war with. Facts and figures could only predict so much and the reality of the situation was that the military needed to figure out ways to get more food to their men more efficiently. Shipping was one of the most difficult problems to overcome. None of the powers had enough ships, especially the Americans, to ship the rations they needed. The AEF relied heavily on food purchased in Europe initially when they arrived in 1917. [25] To free up space on ships new food shipping technology was introduced, including de-boning meat and dehydrating vegetables. These techniques took up less space than previous methods of packing. [26] De-boned beef came in three varieties of 100 lbs. cubes including tenderloins, sirloins, butts, top rinds, and shoulder steaks; prime ribs, rumps, and bottom chucks for roasts; and flanks, plates, blades, necks, shanks, and trimmings for stews. This made meat easier to prep for field cooks as well, since they no longer had to spend as much time prepping and de-boning the meat. [27] Dehydrating vegetables, the creation of soluble coffee, and the expansion of refrigeration were all other technologies that further aided the solution to the shipping problem and became even more common after the war ended. [28]

Not all issues were solved by this new technology. Some were more complicated, like the fact that even before the war began Britain imported most of the food they consumed and the German U-boat attacks and blockades made it even more difficult to import food into the country during wartime. [29] Not to mention with all the men gone to fight in the war there were constant labor shortages in industries where Britain was able to produce their own food. [30] Germans suffered some of the worst food shortages throughout the war because of the scale and scope of the Allied blockade. [31] The French had fewer issues with shortages than they did with damage to their supply and distribution system throughout the war. In 1915 an inspection found that over half of France’s 300,000 field kitchens were completely unserviceable. [32]

Due to issues like these men often got far less than the “official” ration, and as the war went on even less due to supply/distribution difficulties. [33] What food the men of the military did have in the war was usually shared quite freely between soldiers and officers. Comradery was a contributing factor, but it was also a burden to carry extra food around with them, especially food that was sent in care packages. [34] Travel troops that were not in distance of a cooking facility had a diet of bread, canned corn beef or corned beef hash, baked beans, canned tomatoes and roasted or ground coffee. If coffee was unavailable men were given twenty-one cents a day to purchase liquid coffee. [35] When troops were near serviceable kitchens, they received more elaborate meals like chipped beef on toast (commonly known as SOS among the troops) and had access to purchasing extras like candy at canteens. Candy was eventually a part of official overseas rations for U.S. troops in December of 1918. [36]

Food provided to the American draftee in training were some of the most complete meals that the soldiers would receive before going into battle. The menu from Summer of 1917 at Fort Riley gives an excellent example of a typical daily ration for the trainees:

Breakfast- Cantaloupes, corn flakes, sugar and milk, fried liver and bacon, fried onions, toast, bread, and coffee

Dinner- Beef à la mode, boiled potatoes, creamed cauliflower, pickles, tapioca pudding, vanilla [sic] sauce, bread, and iced tea

Supper- Chili con carne, hot biscuits, stewed peaches, and iced tea [37]

Pork and beans were a more common “prepared” meal in a can that troops would receive once deployed, which they could warm up or eat cold. It was similar to today’s baked beans, made with haricot beans and pork fat. [38]

Soft and hard breads were also a staple of all militaries. Bakers had the ability to bake both soft and hard breads, but as the war went on hard breads became more common because it was less prone to damage while transporting it, though it did take longer to bake because of how much denser it was. [39] During the war, one of the best field bakeries output was from a U.S. bakery company. They baked 12,096 lbs. of field bread a day at their peak. [40] The United States troops had a bakery company of around 61 personnel (which would be reduced to 48 during peacetime) for every division of men and used the Manual for Army Bakers for their recipes. [41] Hard breads were also known as “field bread” or “army biscuits” depending on the way they were produced, packaged, and consumed. The army biscuit of the Royal Artillery was “so hard you had to put them on a firm surface and smash them with a stone or something” according to one private. [42] Soldiers came up with many different methods to serve the biscuits including smashing them to a pulp and adding sultanas to make a mushy substance that they would then boil in a sandbag. When it was finished each man would take a sawed-off piece, sandbag still intact. [43]

World War One also saw the development and refinement of the emergency ration. Sometimes these were called iron rations [44] or Armour Emergency Rations, named after the company that produced them. [45] These rations were meant to be food that the troops could fall back on in case of an emergency where other food was not accessible or they were cut off from their supply lines. These products weren’t the most appetizing and it was a general rule that soldiers could not consume their emergency rations without officer permission. [46] European iron rations consisted of a tin of bully beef, tea and sugar, a few biscuits, and a wedge of moldy cheese. [47] American Armour Emergency Rations were just as bad. They consisted of three cakes made of parched wheat and powdered beef and three cakes made from chocolate and sugar. The beef cakes could be eaten dry or boiled in three pints of water for soup, and one pint of water for a porridge substance, or even sliced and fried up. The chocolate cakes were either eaten dry like candy or made into a drink by adding it to hot water. [48]

Substitution during the war was boiled down to a form of art, so to speak. Soldiers often were unable to get the original foods that their rations were supposed to consist of, so the military came up with lists of foods that could be used instead to substitute the original products. Soft bread made from flour often had to be substituted with hard bread or 50/50 bread, fresh meat with canned meat or pickled fish, dried fish, or canned fish, fresh vegetables with desiccated vegetables, and fruit was to be 30% prunes when possible. [49] The Turnip Winter of 1916-1917 was one of the most notable examples of army substitutions. Due to food shortages, the German army was forced to eat turnips in nearly everything, which was commonly thought of as animal fodder or face starvation. They ate bread made of ground turnips and sawdust with mashed turnip paste on top for flavor. They also resorted to horse meat stew with nettles, commonly called “barbed wire entanglements” as their vegetable source. [50] The Germans, also due to shortages, reduced their meat ration from twelve ounces to six ounces over the course of the war, eventually only consuming meat about nine days out of the month. [51]

Food for men in the war could be scarce, often face substitutions, or even be cut but much of the food soldiers did receive was undesirable in taste, quality, and variety. Canned meats were often regarded as disgusting, like the French’s “monkey meat” (a nickname given to the unidentifiable canned meat claimed to be pressed beef the French received in rations, and eventually American soldiers as well) [52] or the British’s Maconochie. Maconochie is referred to as such because of the company’s name emblazoned across the can in which it came. It was a mixture of sliced turnips and carrots with gravy described by one officer as “warmed in the tin, Maconochie was edible; cold it was a mankiller”. [53]

Even simple things like tea were often foul-tasting due to packing and preparation methods. To save room the tea was packed mixed in with sugar, which frustrated soldiers who wanted to separate out their sugar to use in other things.[54] Since all of the foods and drinks were generally prepared in two large vats by field cooks the tea often tasted like meat and vegetables or like the chloride of lime used to sterilize the water. The fact that food and drinks were often transported in petrol cans and canteens were nearly impossible to properly clean did not bring any relief to soldiers seeking a warm cup of tea that tasted like tea. [55]

The repetitive nature of meals in the army was also universally disliked, though there were few options to remedy this due to the all-around supply issues the militaries faced. Jam was one food often complained about. The British jam company Ticklers produced jams originally in plum and apple, eventually also expanding to gooseberry and rhubarb, but these bland flavors did little to make men happy, especially when they used jam near-daily. Men wondered when strawberry or raspberry jam might be introduced to mix things up, but they never were. [56] Estaminets behind front lines often only served fried eggs with chips or omelets, earning the whole La Bassée Sector the nickname of the “Egg and Chip Front”. [57] The care boxes soldiers received from their families were often the highlight of their diets, varying things with some good fresh food from home, as one soldier describes in a thank you letter to his family:

You can not really appreciate what it means to me or would mean to any man down here. The meals are very much alike and plain. Now I can answer the mess call with a jar of heavenly jam under my arm and a piece of cake or pie for dessert and you don’t know how it will add to the meal. The other things—all those nuts and apples and oranges and raisins and pudding and salad and cocoanut and what not—I was simply overwhelmed when I unpacked the box. [58]

Sometimes it was the small things, like variety, that kept soldiers going through the war.

Drink was also an important ration to the men of the First World War. Every army in World War One received a form of alcohol rations for their men except the Americans, who were forbidden alcohol for fear of moral compromise and drunkenness. [59] British drink rations included one earthenware gallon-sized jug of rum a day per every sixty-four men. The bottles were marked “SRD” for “Services Rum Diluted” which soon came to be known as “Soon Runs Dry” by British soldiers, a more fitting translation in their eyes. [60] German and French had a ration more closely related to brandy, called “98%” by the Germans, who received 0.17 of a pint daily. French gnôle was described as a “cross between methylated spirits and paregoric elixir”.[61] French and German troops also had official wine rations which the French referred to as le pinard and frequently replaced water within their canteens. [62] The drunkenness that American military leaders feared from their soldiers should they have access to liquor was largely a non-issue. Though occasionally there were court martial cases involved in drunkenness and alcohol was used by some men to self-medicate, for the most part, disorderly conduct due to alcohol was so infrequent it was hardly an issue. [63]

Difficulties in the Trenches

Nowhere were supply issues more apparent than in the trenches. [64] Rear areas frequently had significantly better diets than that given to the soldiers suffering the hardships of the frontline positions. [65] Since trench warfare had very specific conditions men usually faced their rations too, had to reflect that. From gas attacks, sanitation issues, and the lack of fires allowed in the trenches to cook foods, regular meals were made difficult. The America trench ration included a one-pound can of meat (bacon or corned beef), two eight-ounce tins of hard bread, two and a half ounces of sugar, a little over an ounce of coffee, and a little less than a fourth of an ounce of salt. This amounted to 3,300 calories a day in a difficult to carry cylindrical tin can. The containers were galvanized to protect them from gas and could also be used to float two men in the sea at a time. [66] Soldiers often referred to the canned salmon that was sometimes placed in their trench rations as “goldfish” and the can of meat as “canned willie”. [67]

Getting food to soldiers while it was hot was near impossible. Field kitchens were not even brought close enough to the front lines to provide troops with food until 1915. [68] When field kitchens came closer to the trenches food was carried to the soldiers in dixies, petrol cans, and jam tins, all packed into straw-lined boxes. This food usually arrived to the soldiers cold. [69] Hot soup, commonly known as “slum”, stew, and coffee were brought as close to the men as possible by ration runners on two-wheeled carts drawn by two mules. Then the food was carried into the trenches on a pole by two men. [70] The luxury of carts was not always available either. In 1914 French cooks had to crawl as close to the trenches as they could get and throw food down to the men. [71] Inevitably, being a ration runner was a dangerous job and many men died trying to bring food to the soldiers. [72]

Fire was banned in the trenches because smoke was likely to give their position away to enemies. [73] This was unfortunate due to the lack of ways to heat or reheat certain food and drink items, offering comfort and sometimes sanitation to men. Some men used improvised cookers, which were rifle pull-through rags soaked in whale oil that would be lit in a cigarette tin. The flame lasted just long enough to heat a mess tin of water, which was sometimes gathered from the bottom of shell holes when fresh supplies ran out. Boiling the water was the only way to ensure some level of sanitation since it was often tainted by gas or rotting corpses. [74] Luckier men made use of Tommy Cookers, which were pocket size solidified alcohol stoves which gave off a slow and weak heat hardly any better than the improvised cookers. [75]

The Battle for Food on the Home Front

The militaries of every power faced the inevitable issue of certain foods being lost, pilfered, or thrown away before they reached the troops [76], but the American government faced a larger issue overall with their food—the quality. The Pure Food and Drug Act was enacted in 1906, well before the start of the First World War, but played a huge factor in the war when the Food Administration was created to enforce the act. [77] The Food Administration, now known as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), can be described as a series of “crisis-legislation-adaption cycles”. [78] The Spanish American war and meat packing industry abuses were just two of the reasons the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed, consumer protection becoming a necessary action for the government to take, especially when it endangered the health and safety of soldiers in the future war. [79] When the act was passed there was little done to actually enforce its policies [80] which was why in 1917 Woodrow Wilson established the Food Administration. The Food Administration, headed by Herbert Hoover, was to control the production, processing, distribution of meats, fats and oils, wheat, sugar, milk, fruits, and vegetables, all valuable commodities during wartime. [81] This process was aided by food and drug reviews also carried out by the Food Administration. [82]

At home, each and every power had their own ways of ensuring food got to their soldiers through civilian centered propaganda techniques that encouraged people to waste less and make more of their own food to save most of it for the men fighting. Hooverization, as it was called at the time, was one of the most effective of these propaganda campaigns. It was Hoover’s plan to conserve food without rationing. Hoover claimed, “voluntary action has the great value of depriving those who can afford it and not those who have no margin for sacrifice.” [83] Hoover’s plan was directed at and embraced by the middle class, especially women due to their caring and domestic nature. [84] Who was better suited to take care of the boys off fighting than women at home? He believed that the fighting of the war was one of the greatest national tasks ever presented to the American people and that through their acceptance of this task, victory was made possible. [85]

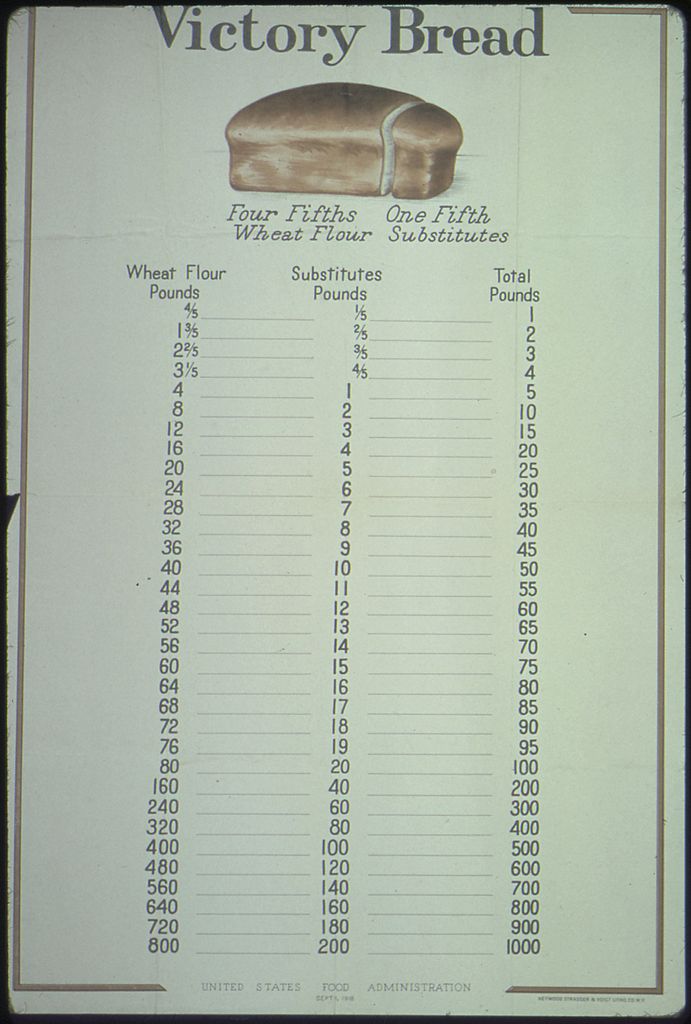

The domestic sciences, which was largely marketed toward women to help with nutritious meal prep and focused on new research about caloric intake and balanced diets, were more popular than ever at the turn of the century. [86] Women who studied and mastered these skills could make things like victory bread or 50-50 bread, which used substitutes for 20% or more of the ingredients typically in bread. [87] This meant that the ingredients they weren’t using were able to be provided to soldiers. In the summer of 1918 when there was an overabundance of potatoes produced American housewives made potato bread instead of wheat bread. [88] Hoover emphasized that Americans needed to eat less wheat, meat, fats, and sugar at home. [89] Popular posters embodied that sentiment with slogans like “Eat Less of the Food Fighters Need”. [90] Women mostly, but also men who did not fight in the war, worked in many different food production jobs [91] and even grew their own gardens at home to help supply soldiers while using less of that supply. [92] Posters, radio, and cinema reels promoted the ideal involvement of the civilian [93] and led to the popular movement of planting these gardens at home, known as Victory Gardens. They also canned their own foods to make what was grown in the gardens last even longer. [94] The American Food Administration ended up reducing the domestic consumption of food by 15% without ever having to institute civilian rationing. They used their propaganda, patriotism, and organization to their advantage. [95]

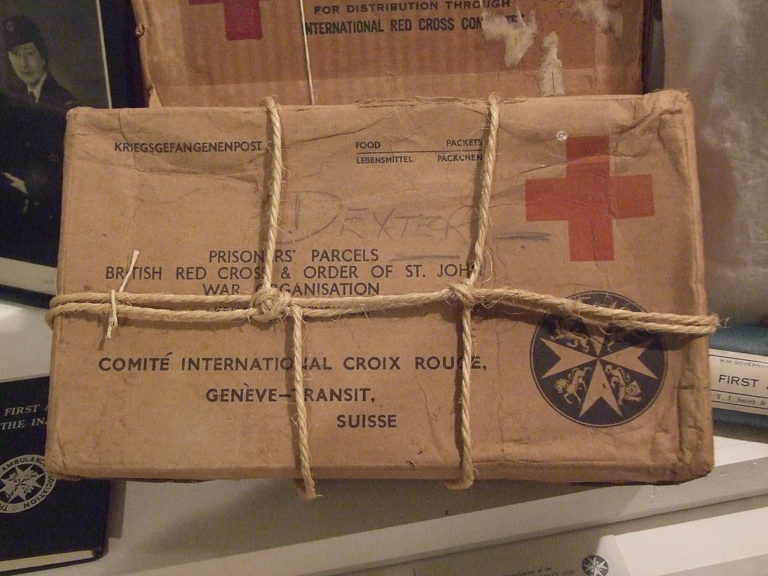

Non-military organizations were also very involved in the war effort, ensuring that rations were not the only way soldiers got their food. Aside from military surplus depots [96], many organizations like the Red Cross, YMCA, Salvation Army, National Catholic War Council, Jewish Welfare Board, War Camp Community Service, and the American Library Association provided other food for men on the front lines or moving out to fight. [97] The Red Cross, YMCA, and Salvation Army were some of the most successful in providing aid to soldiers on a large scale. [98] The Red Cross began their Canteen Service in 1917 which gave troops food, snacks, and leisure activities while in transit at ports and railway depots. They also had mounted rolling canteens to get food out to the men already on the field. [99]

The YMCA became known for producing cookies, milk chocolate bars, caramels, jam, drinking chocolate, sweet chocolate bars, chocolate cream bars, and nut covered chocolate rolls in their own factories for the troops. The YMCA sold these goods at wet canteens throughout Europe. [100] The Salvation Army was perhaps the most highly regarded aid organization among soldiers. They were known for their good cheer and serving lemonade, coffee, cakes, and pies, but most importantly doughnuts to the men. [101] The Knights of Columbus, War Camp Community Service, Jewish Welfare Board, YWCA, and the American Library Association provided smaller scale assistance like giving coffee, chocolate, and chewing gum to soldiers. [102]

Without the combined effort on the behalf of so many different governments, businesses, organizations, and people the soldiers of World War One would have been in a much more dire situation. All these factors allowed troops to receive the food they needed to fight and in the case of the Allied powers, food really did win the war. Each power did their best to overcome the issues of shortages, shipping and delivery problems, and to give soldiers a better quality of food that would have been provided in previous wars. Food was, and always will be, one of the most important factors of the First World War and paved the way for even more important advances in technology by the time World War Two came about. Without the discoveries and developments of methods for food distribution and production during the war, society would be in a much different place than it is today.

Sources

[1] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military: A History (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2011), 142.

[2] Kingsbury, Cecilia Malone. For Home and Country: World War I Propaganda on the Home Front (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), 41.

[3] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 115.

[4] Ibid. 128.

[5] Ibid. 116.

[6] Ibid. 115-116.

[7] Ellis, John, Eye Deep in Hell: Trench Warfare in World War I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), 125.

[8] Ibid. 125.

[9] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 117-118.

[10] Ellis, John, Eye Deep in Hell. 125.

[11] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 115.

[12] Ibid. 116.

[13] Ibid. 116.

[14] Ibid. 119.

[15] Ibid. 122.

[16] Ibid. 125.

[17] Ibid. 116.

[18] Ibid. 118-119.

[19] Coffman, Edward M. The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968), 36.

[20] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 124.

[21] Ibid. 124.

[22] Ibid. 120.

[23] Kingsbury, Cecilia Malone. For Home and Country. 41.

[24] Ibid. 41.

[25] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 123.

[26] Ibid. 123.

[27] Ibid. 123.

[28] Ibid. 122-127.

[29] Hockenhull, Stella. “Everybody’s Business: Film, Food and Victory in the First World War.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 35, no. 4 (2015) 580-581.

[30] Ibid. 580.

[31] Ellis, John, Eye Deep in Hell. 127-128.

[32] Ibid. 127.

[33] Ibid. 127.

[34] Ibid. 132-133.

[35] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 117.

[36] Ibid. 118-119.

[37] Coffman, Edward M. The War to End All Wars, 65.

[38] Ellis, John, Eye Deep in Hell. 129.

[39] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 120.

[40] Ibid. 120.

[41] Ibid. 119.

[42] Ellis, John, Eye Deep in Hell. 129.

[43] Ibid. 129.

[44] Ibid. 127.

[45] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 117.

[46] Ibid. 117.

[47] Ellis, John, Eye Deep in Hell. 127.

[48] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 117.

[49] Ibid. 116-117.

[50] Ellis, John, Eye Deep in Hell. 129.

[51] Ibid. 128.

[52] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 125.

[53] Ellis, John, Eye Deep in Hell. 129.

[54] Ibid. 129.

[55] Ibid. 130-131.

[56] Ibid. 130.

[57] Ibid. 132.

[58] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 131.

[59] Ellis, John, Eye Deep in Hell. 134.

[60] Ibid. 133.

[61] Ibid. 133.

[62] Ibid. 133.

[63] Ibid. 134-136.

[64] Keegan, John. The First World War (New York: Vintage Books, 2000), 136.

[65] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 130-131.

[66] Ibid. 118.

[67] Ibid. 118.

[68] Ellis, John, Eye Deep in Hell. 125.

[69] Ibid. 125.

[70] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 123-125.

[71] Ellis, John, Eye Deep in Hell. 127.

[72] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 125.

[73] Ibid. 130-131.

[74] Ellis, John, Eye Deep in Hell. 127.

[75] Ibid. 127.

[76] Ibid. 125.

[77] Borchers, Andrea T., Frank Hagie, Carl L. Keen, and M. Eric Gershwin. “The History and contemporary Challenges of the US Food and Drug Administration.” Clinical Therapeutics 29, no. 1 (2007) 2.

[78] Ibid. 1.

[79] Ibid. 2.

[80] Ibid. 6.

[81] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 115-116.

[82] United States. Food Drug Administration. History Office. A Guide to Resources on the History of the Food and Drug Administration. (2002).

[83] Kingsbury, Cecilia Malone. For Home and Country. 27-31.

[84] Ibid. 28.

[85] Ibid. 54.

[86] Ibid. 50.

[87] Ibid. 53.

[88] Ibid. 29.

[89] Ibid. 52.

[90] Ibid. 52.

[91] Ibid. 46.

[92] Hockenhull, Stella. “Everybody’s Business: Film, Food and Victory in the First World War.” 589.

[93] Ibid. 579.

[94] Fisher, John C. & Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military. 145.

[95] Ibid. 142-143.

[96] Ibid. 119.

[97] Ibid. 127-128.

[98] Ibid. 128.

[99] Ibid. 128.

[100] Ibid. 129-30.

[101] Ibid. 129.

[102] Ibid. 130.