Top 5 Historical Disasters of Racine County

Racine County was once one of the most populated towns in Wisconsin. It was the center of manufacturing, shipping, inventing, scientific advancements, and leisurely activities. Back in the days of old, so to speak, Racine was filled with things to do, places to go, and sites to see. Still, this did not stop Racine’s residents from pursuing one of their favorite pastimes—disaster spectating. It should come as no surprise to those who know about how popular public executions were to watch that people are drawn to the gruesome and curious nature of death and disasters. Today we’ll be taking a look at the top five historical disasters of Racine County and take a journey of our own to fulfill our morbid curiosities.

#5: Winter of 1912

DEATHS: 0 | INJURIES: unknown | FINANCIAL LOSSES: unknown | DATE: March 3-8, 1912

Winter is hardly ever a fond memory for Wisconsinites–it’s more like a looming inevitability. The Winter of 1912 in Racine, Wisconsin was more like a bad dream that residents would never forget. Many captains, sailors, and lighthouse keepers recalled the Winter of 1912 as one of the worst in Racine’s history. [1] The winter was rough through the months of January and February, the temperature dropping below zero 27 times in less than 45 days. [2] Racine’s harbor, the center of the town’s livelihood, had completely frozen over and winds were howling at nearly 60 mph from the northeast. [3] Nearing the end of February things finally began looking up for Racine. Then two of the worst storms in Racine’s history hit. [4]

On March 3, 1912 two lake steamers by the names of the Racine and the Iowa became trapped in the ice off Racine’s harbor with crews of around 75 men trapped inside. The ships had been headed to Milwaukee when they became trapped in the ice floes a mere one and a half miles from one another and about the same distance from shore. [5] The winds were particularly harsh that day and the ships decided to try to wait out the bad weather in Racine’s harbor. Unfortunately, whilst trying to get back to the harbor, each of the ships became stuck in nearly fifteen feet of blue ice. [6] When word spread around of the ships’ circumstances, hundreds of Racine residents came out in the chilly weather to look at the ships trapped in the ice. [7]

Residents were lined up between 10th and 15th Streets to watch the spectacle. Sailors were not as thrilled, however. Daniel Hoey, a sailor on one of the stuck ships, reportedly walked to shore to go purchase tobacco for his vessel. He made it about a mile using a broomstick as assistance but as he tried to jump over an area of open water he lost his footing and fell in. According to accounts he pulled himself out, continued his journey and got his tobacco and returned to the ship. [8] It wasn’t until the following day, on March 4th that rescue was attempted. A tugboat by the name of Langlois was sent to rescue the Racine but it too became stuck in the ice. [9]

As time went on with no progress in rescuing the ships, Racine residents became more daring and tried to approach the ships themselves. John Campbell, a sailor aboard the Iowa, recounts what he saw from his ship, “About 500 men and boys walked across the ice from the end of Thirteenth St. to see the ships imprisoned in the immense ice floes… I remember reading that scores of boys broke through air holes in the ice and were soaked and chilled before getting ashore and home.” [10]

After five days of being stuck in the ice, the ships were finally rescued on March 8th. Rescuers had dynamited channels around the ships large enough for them to return back to shore and the winds had shifted enough that the ice floes were no longer piling up as badly. [11] On March 7th the Racine Journal-News offered its opinion on the whole spectacle, “The reckless manner in which children and young men venture on the ice in Lake Michigan in order to get near the steamers and tug may result in loss of life. Yesterday afternoon 100 trooped across the frozen water, and while ice was being dynamited stood close by. A number of boys fell through holes into the water and would have drowned had companions not pulled them out.” [12]

#4: The Train Wreck of 1891

DEATHS: 2 | INJURIES: 50-60 | FINANCIAL LOSSES: $200,000-$250,000 | DATE: March 24, 1891

Racine’s prime location between Milwaukee and Chicago have always made it a hub of locomotive activity. This was never truer than in the late 1800s when business was booming in the city. Multiple major transportation lines crossed through the city regularly, both carrying both freight and passengers. That being said, Racine was no stranger to train wreckages. With the number of trains coming through the city on a daily basis, there was bound to be accidents. One of these accidents was particularly memorable and came to be known as the Wreck of 1891.

Back in the 1890s it was customary for trains to all come to a full stop within 400 feet of the St. Paul railroad crossing. [13] It was on March 24th, 1891 that this rule was violated and one of the nastiest train wrecks in Racine occurred. A southbound freight train that had pulled onto the main line to take water was being backed into the siding to make room for an incoming northbound passenger train when the crash occurred. The freight train was nearly in the clear when the passenger train came barreling down the tracks at 40 mph, seemingly unable to stop. [14] The head brakeman aboard the freight train went onto the tracks with his red lantern to try and signal the passenger train to come to a stop, but when it became clear that he could no longer safely remain on the tracks he hurled his lantern at the locomotive and jumped off the tracks. [15] The trains collided head-on, reared up into the air and swayed an instant before they both came toppling down onto the east side of the tracks, destroying the wooden platform at the junction. The debris from the passenger and baggage cars burst into flames moments later. [16]

Later in court, D.E. Burke of Milwaukee, the engineer of the passenger train, testified that he tried to apply the brakes multiple times before the 400-foot sign but when it became clear that they were not working he tried to reverse the train but the lever failed to catch and the train continued to barrel forward. It was later determined that the wreck was caused by the failure of the air breaks to work, though the cause of the failure itself was never identified. [17] There are conflicting reports of the number of passengers injured in the wreck, ranging from 50-60. It is said that hospitals were at maximum capacity and drug stores nearby reported a boom in business immediately following the wreck. [18] Those who escaped with minor injuries were the lucky ones.

William Roe of Kenosha, an engineer on the passenger train jumped to the west as the crash occurred and escaped with only minor injuries. [19] Those who jumped to the east were not so fortunate. John Gobben of Milwaukee, a fireman aboard the passenger train leaped out of the train as they were about to collide but instead was caught up within the wreck and badly wounded. He was rushed to St. Mary’s Hospital but died of his injuries about 22 hours later. [20] Willis Andres, a resident of Crystal Lake and a fireman aboard one of the trains, met a similar fate. When he saw that a collision was inevitable he jumped out of the train but was quickly buried beneath the wreckage. When his body was finally recovered several hours later it was reportedly “badly mangled.” [21]

Word of the train wreck spread quickly and soon hundreds showed up to look at the fiery wreck. One witness, Milt M. Jones, an amateur photographer with one of the first box cameras produced that used roll film, even got a few snapshots of the wreckage that quickly became in high demand as souvenirs. [22] The congestion caused by the crowds of onlookers made it difficult for emergency services to reach the wreck and one fire engine even became stuck in the mud on its way to the scene. [23] Loss of life and injuries were not the only problems victims of the wreck had to face. As more spectators came to look at the crash, so too did looters looking to capitalize off of the tragedy. Passengers complained of jewelry and money theft and even reported seeing spectators trying to rob beer bottles that had been being transported on the freight train. [24] A New York salesman reported losing over $2,000 worth of merchandise in the fire [25] and over $6,000 of money that had been on the train had burned up within an overheated safe. [26] Overall, losses were estimated between $200,000-$250,000 and both locomotives were deemed unsalvageable. [27]

#3: The Blake Opera House Fire

DEATHS: 3 | INJURIES: unknown | FINANCIAL LOSSES: $197,000 | DATE: December 28, 1884

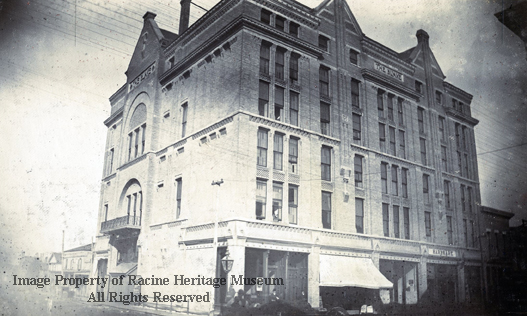

Many large cities back in the day had multiple entertainment venues to occupy their citizens’ leisure time. One of the most popular of these venues, especially in Racine, were opera houses and theaters. The Blake Opera house was built in 1882 and praised for being the finest venue in the state. [28] The opera house resided at the northeast corner of Sixth and Barnstable Streets [29] and was a popular destination for the citizens of Racine. The night of the fire a production of The Beggar Student had been going on just hours earlier. [30] On the frigid evening of December 28th flames were to be discovered shortly after midnight [31] when two explosions rocked the building. Within moments fire had engulfed the northeast end of the building. [32] The flames quickly ate away ate the ornamental façade of the opera house along with adjoining hotel, which at the time of the fire was filled with guests. [33]

It wasn’t until 1:05am that the first alarm was sounded by a police officer who spotted the flames from his post on Main and Fifth Streets. By 1:15am six steamers from the fire department were pumping water at the blaze, including a steamer by the name of “L.S. Blake.”[34] Efforts shifted from trying to extinguish the fire to trying to prevent the spread of the fire due to the cold winds that made it impossible to stop. [35] Hundreds of residents from nearby turned out at the late hour to watch them battle the fire. Women in nightgowns, children, and men were all witnessed running from the building in a panic. [36]

Spectators even claimed to see a woman hanging out of a fourth story window screaming for help. Allegedly someone shouted to her “jump for your life” but it was too late as another explosion was heard and the woman was swallowed in flames. [37] This was likely the housekeeper, Mrs. Patricks, who was one of three killed in the fire. The servant’s quarters in the upper story of the hotel were one of the first to be cut off when blazing rafters fell, making escape impossible. [38] Two others, a husband and wife that were both a part of the Thompson Opera Company were lost to the fire. Mr. and Mrs. Glover’s bodies were not recovered until several days later [39], reportedly found clutching one another in their charred state. [40]

Aside from the loss of life the fire did an estimated $197,000 worth of damage. [41] What little insurance money that was received after the disaster was split between stockholders and the lots where the opera house once stood were to be sold off to the highest bidder. Even coins found in the wreckage were sold to spectators as momentous of the tragedy. [42] The Thompson Opera Company reported $6,000 in damages [43] and multiple benefits were hosted on behalf of the survivors of the fire. [44] Though morbid, Racinians were grateful that the fire happened as late as it did, rather than when the opera house was still filled with guests from the show. They were relieved that the loss of life was not greater from such a disastrous fire. [45]

#2: The Blaze of 1882

DEATHS: 1 (indirect) | INJURIES: unknown | FINANCIAL LOSSES: $750,000-$1,000,000 | DATE: May 5, 1882

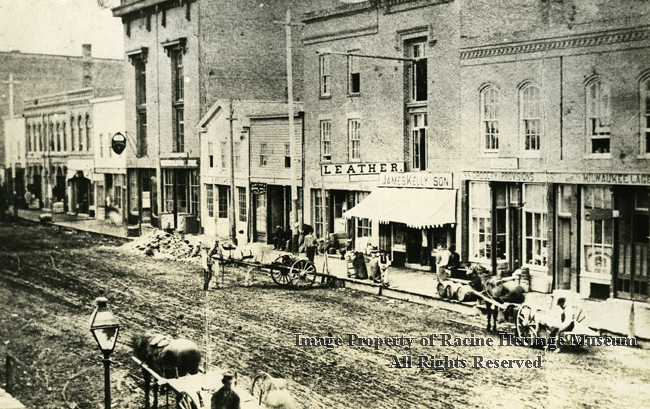

The Blaze of 1882 was Racine’s most devastating fire. It began in the evening of May 5th, 1882 and was not stopped until late the next afternoon. [46] Winds were coming from the northeast at nearly 20 mph and causing destructive waves to crash against the harbor. [47] Out in the dock sat the tugboat called Sill, near the Goodrich warehouse. It was when sparks went flying from the smokestack and landed on the roof of the warehouse that the fire began. [48] Around 10:00pm people began smelling smoke [49] and at 10:45pm the fire was first reported. [50]

The fire first consumed the Goodrich Transportation Company warehouse which was located on the south harbor pier near the shore. [51] The warehouse was filled to the brim with dry goods which acted like kindling to the fire [52] which smoldered in the building for at least one hour before breaking through the roof. [53] Nearby was the abandoned Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad Company’s grain elevator, towering around 156 feet tall. The fire had no problem making its way from the warehouse to the grain elevator, eating away the structure and hardly giving firefighters a chance to stop the flames before they reached the next-door lumber yards. The Jones, Knapp & Co. and Kelly, Weeks & Co. both lost over 10 million feet of lumber to the fire.[54] Schooners that were docked nearby were in danger of burning up from the magnitude of the fire and had to be moved away from the harbor. [55]

At the time the fire department only had two horse-drawn steamers which were completely inadequate for dealing with the flames. [56] The Racine Daily Journal equated the steamers to “squirt guns” in the face of the flames. [57] Without proper firefighting equipment, the fire grew large enough to be seen from Milwaukee and a schooner captain in Two Rivers even reported being able to see it. [58] The fire threatened to burn D.P. Wigley’s building, which at the time housed a linseed oil factory known as Emerson & Co. [59] and if it could not be contained before it reached that building it could even reach as far as Monument Square. [60] Unfortunately, the flames did reach Congress Hall, a premier hotel in the city which Mary Todd Lincoln had stayed for a few weeks in 1867 after her husband died. The building was lost. [61]

The bluffs near Chatam Street prevented firefighters from being able to access the lake [62] and by 11:30pm Mayor William Packard realized the city was in trouble and called Milwaukee for assistance. [63] A train carrying help from the Milwaukee Fire Department arrived around 2:45 am and a shoe shop building was dynamited to help stop the advance of the fire. [64] At 4:30am trains carrying men and equipment from Chicago’s fire department also arrived. Though the fire had mostly been stopped on Main Street it was still burning on Wisconsin Street. [65] Even Kenosha’s fire department is said to have assisted in fighting the flames [66], and by 5:00am the fire was under control. [67] Still, the fire was not completely extinguished until around 2:00pm. [68]

Miraculously, the only death attributed to the fire was that of an elderly woman, who reportedly died of a heart attack from the shock of the fire. [69] Sadly, the loss of homes and businesses were immense. Over 44 buildings had been completely destroyed in the fire [70] and dozens of families were left homeless. [71] Financial losses directly after the fire were exaggerated but as things calmed down loss estimates were still anywhere from $750,000 to $1,000,000. [72] Only $300,000, or about a third of the loss, was covered by insurance. [73]

Looters also made off with thousands of dollars’ worth of goods during the chaos of the conflagration. [74] Stocks had been moved outside of buildings and into the streets to keep them from the damage of the fire. Unfortunately, they were largely unprotected. Among the goods stolen newspapers reported that coffins, over 52 pairs of boots, and many raw materials for shoe production had been stolen. A firefighter visiting from Milwaukee was even witnessed to have stolen a roll of felt from Miller Boot Co. to use as a horse blanket. [75] The Racine Daily Journal called for looters to return their stolen goods to their rightful owners. [76] Out of all the damage caused by the fire there was one silver lining. Racine residents demanded the fire department be equipped with more up to date firefighting technology [77] and new equipment was purchased shortly after the fire. [78]

#1: The Cyclone of 1883

DEATHS: 7-10 | INJURIES: 85-100 | FINANCIAL LOSSES: $70,000 | DATE: May 18, 1883

The cyclone that hit Racine in 1883 was the first that had touched down in the county since its settlement. [79] Previously it had been believed that due to its lakeshore location Racine was immune to the path of cyclonic storms. [80] Residents soon found out that this long-held belief was incorrect. At 4:00pm on May 18th, an electrical storm began to brew in the sky and temperatures were unusually cool for the season. [81] By 5:30pm the sky had gotten unusually dark and the temperature rose rapidly. [82] At 7pm the tornado touched down, coming from the southwest. [83] First, it uprooted farms outside of the city before moving to Horlick’s Food Factory and the Mt. Pleasant School, destroying all within its path. [84]

The path of the tornado was about three city blocks wide [85] and took a northerly path toward the residential areas of Racine, destroying homes and businesses. [86] The few houses that had existed between Horlick’s Food Factory and the city were gone. The scope of the tornado’s damage had exceeded anyone’s expectations, destroying all of the north side of High Street and Douglas Avenue [87], to Flat Iron Square, making it to the west side of North Main Street at its furthest reaches. [88] Most of the homes that had been destroyed were made of wood, but several were also brick, showing the true power of the tornado. [89] Anvils, farm equipment, and other heavy machinery had been thrown about as if it were nothing [90], including a house that had been picked up and carried onto the Northwestern train tracks, delaying trains for nearly a day. [91] When the cyclone finally passed into Lake Michigan it created water spouts nearly 300 feet high [92] that witnesses described as “beautiful.” [93]

Most residents who were able to reach their cellars were safe from the storm’s full force, but those who were still outside when it hit were not so lucky. [94] Victims included men, women, and children alike and estimates of those killed by the tornado ranged from 7-10 individuals. [95] One young girl was picked up by the wind and thrown against a home, instantly being killed. [96] Another incident that had originally been seen as a miracle soon became a tragedy. Fourteen people had made it safely out of Petura’s Grocery Store when the building was ripped apart by the winds. Unfortunately, the following day the bodies of two young sisters sent to fetch groceries before the storm hit, were found beneath the wreckage. [97] Their ages were six and eight years old.

Somewhere between 85 and 100 people were injured in the cyclone and that night both the living and dead were removed from the rubble. [98] The bodies of those that had died were guarded overnight until they could be taken to the courthouse the following day [99] and those that were injured, 31 of which were considered dangerously injured [100], were taken to St. Mary’s and St. Luke’s Hospitals for treatment. [101] Over 250 people were made homeless [102] and over 128 homes and buildings were destroyed.[103] Many of those who were victims of the storm were foreign-born laborers who had now lost everything. [104] Losses were estimated at $70,000. [105]

The following day ruins were visited by people of all different localities, many of them venturing on train from Kenosha, Chicago, Waukegan, and Milwaukee. One year after the great blaze Racine had once again become a target for spectators and looters. [106] Everyone wanted a part in the drama, prompting many to make up their own stories of how they were involved in the windstorm. In one newspaper a fifteen year old boy had his own tall tale told: “John Schootens, a boy about 15 years old, declares that he was taken up by the wind, carried far away from the starting point and landed in a mud puddle clear up to his chin. Being unable to pull himself out, and no one coming to perform that office, he philosophically made the best of circumstances and slept warm and comfortable all night. In the morning he was seen by a passer by and extricated. Some say the boy lies.” [107]

Racine’s Common Council immediately pulled into action, trying to provide relief for those that had become victims of the storm. [108] Temporary shelter was offered at the Blake house and many found refuge with neighbors and relatives that were unharmed by the cyclone. [109] Within a short amount of time a Tornado Relief Association was formed and many of the prominent and wealthy men in the city donated. They managed to collect a grand total of $20,340 for those in need. $17,007 was spent on those in need, 19% going towards personal property lost, 57% going towards lost dwellings, 2% going toward sundry bills, and 5% for wounded parties. The remaining 17% was put toward a fund for the relief of future disasters.[110] With the spirit of community, Racine once again collected itself and moved on from yet another tragedy.

Sources

[1] “Veteran Sailors Declare Winter One of the Hardest in 20 Years,” The Racine Review (Racine, WI), February 8, 1929.

[2] “Winter-Weary Racine Long Remembers Below-Zero Weather and Storms of 1912,” The Racine Journal Times (Racine, WI).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Photos of Racine Train Wreck of 1891 Published for First Time,” Racine Journal Times (Racine, WI), December 5, 1937.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] “Wreck at the Junction,” Racine Journal Times (Racine, WI), October 14, 1956.

[27] “Photos of Racine Train Wreck,” Racine Journal Times

[28] “Death in the Flames,” The National Police Gazette: New York (New York, NY), January 17, 1885.

[29] File 1, Folder 1. Fires (General) Vertical File. (Racine Heritage Museum, Racine WI)

[30] “Weird Wreck,” Racine Daily Journal (Racine, WI), December 30, 1884.

[31] “Death in the Flames,” The National Police Gazette

[32] “A Night to Remember,” Retrospect (Racine, WI)

[33] “Death in the Flames,” The National Police Gazette

[34] “A Night to Remember,” Retrospect

[35] Ibid.

[36] “Death in the Flames,” The National Police Gazette

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] “Removing the Ruins,” Racine Daily Journal (Racine, WI), January 2, 1885.

[40] “Death in the Flames,” The National Police Gazette

[41] “Remembers Opera Fire 65 Years Ago Today,” Racine Journal Times (Racine, WI), December 28, 1949.

[42] “Weird Wreck,” Racine Daily Journal

[43] “Death in the Flames,” The National Police Gazette

[44] “Remembers Opera Fire 65 Years Ago Today,” Racine Journal Times

[45] “Weird Wreck,” Racine Daily Journal

[46] “Old Photograph Shows Stores on Main Street Which Were Destroyed n the Great Fire of 1882,” Racine Journal Times (Racine, WI), October 24, 1937.

[47] “100 Years Ago: The Big Fire of ’82,” Racine Journal Times (Racine, WI), 1982.

[48] Ibid.

[49] “The Great Fire,” Racine Daily Journal (Racine, WI), May 8, 1882.

[50] “The Big Fire,” Racine Journal Times (Racine, WI), April 29, 1984.

[51] “Old Photograph Shows Stores on Main Street Which Were Destroyed n the Great Fire of 1882,” Racine Journal Times

[52] “100 Years Ago: The Big Fire of ’82,” Racine Journal Times

[53] “The Big Fire,” Racine Journal Times

[54] Ibid.

[55] “100 Years Ago: The Big Fire of ’82,” Racine Journal Times

[56] Fire destroyed 44 buildings

[57] “The Great Fire,” Racine Daily Journal

[58] “The Big Fire,” Racine Journal Times

[59] “100 Years Ago: The Big Fire of ’82,” Racine Journal Times

[60] “The Big Fire,” Racine Journal Times

[61] “100 Years Ago: The Big Fire of ’82,” Racine Journal Times

[62] Ibid.

[63] “The Big Fire,” Racine Journal Times

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] “Fire Destroyed 44 Buildings On Main Street, May 5, 1882,” Racine Journal Times (Racine, WI), October 14, 1956.

[67] “The Big Fire,” Racine Journal Times

[68] “Fire Destroyed 44 Buildings On Main Street, May 5, 1882,” Racine Journal Times

[69] “The Big Fire,” Racine Journal Times

[70] Ibid.

[71] “100 Years Ago: The Big Fire of ’82,” Racine Journal Times

[72] “The Great Fire,” Racine Daily Journal

[73] “100 Years Ago: The Big Fire of ’82,” Racine Journal Times

[74] “The Big Fire,” Racine Journal Times

[75] “Looters Robbed Downtown During Racine Fire of 1882,” Racine Journal Times (Racine, WI), April 5, 1936.

[76] “The Great Fire,” Racine Daily Journal

[77] “The Big Fire,” Racine Journal Times

[78] “The Great Fire,” Racine Daily Journal

[79] File 1, Folder 1. Windstorms (General) Vertical File. (Racine Heritage Museum, Racine, WI)

[80] “Booklet Tells of Tornado 56 Years Ago,” Racine Journal Times (Racine, WI), May 21, 1939.

[81] “The Centennial of a Killer Storm,” Racine Journal Times (Racine, WI), May 7, 1983.

[82] File 1, Folder 1. Windstorms (General) Vertical File

[83] “Racine Disasters,” Wisconsin Magazine of History (Madison, WI), September 1921.

[84] File 1, Folder 1. Windstorms (General) Vertical File

[85] Ibid.

[86] “The Centennial of a Killer Storm,” Racine Journal Times

[87] “Tragedy Stalked Racine 2 Years in a Row,” Racine Journal Times (Racine, WI), July 1, 1934.

[88] File 1, Folder 1. Windstorms (General) Vertical File

[89] Ibid.

[90] “Booklet Tells of Tornado 56 Years Ago,” Racine Journal

[91] File 1, Folder 1. Windstorms (General) Vertical File

[92] “The Centennial of a Killer Storm,” Racine Journal Times

[93] File 1, Folder 1. Windstorms (General) Vertical File

[94] Ibid.

[95] “Racine Disasters,” Wisconsin Magazine of History

[96] File 1, Folder 1. Windstorms (General) Vertical File

[97] Ibid.

[98] Ibid.

[99] Ibid.

[100] File 1, Drawer 1. Tornado Subject Card File. (Racine Heritage Museum, Racine, WI)

[101] “Racine Disasters,” Wisconsin Magazine of History

[102] Ibid.

[103] “Booklet Tells of Tornado 56 Years Ago,” Racine Journal

[104] File 1, Folder 1. Windstorms (General) Vertical File

[105] File 1, Drawer 1. Tornado Subject Card File.

[106] File 1, Folder 1. Windstorms (General) Vertical File

[107] “Freaks of the Wind,” Racine Advocate (Racine, WI), 1883.

[108] “Racine Disasters,” Wisconsin Magazine of History

[109] File 1, Folder 1. Windstorms (General) Vertical File

[110] File 1, Drawer 1. Tornado Subject Card File.